Depression often exists alongside other mental health conditions, including anxiety and trauma-related disorders, creating complex and overlapping symptom patterns. Major Depressive Disorder (MDD) and Persistent Depressive Disorder (PDD) are two distinct conditions that exist on a spectrum, shaping daily life in different ways.

Understanding the unique challenges of each helps individuals and their loved ones make sense of their symptoms and explore the most effective paths to healing.

Understanding Depression as a Spectrum

The medical understanding of depression has evolved significantly over time. In psychiatry’s earlier days, depression was viewed as a singular condition called “melancholia,” with little recognition of its varying presentations and intensities.

What we now know as Persistent Depressive Disorder was formerly termed “dysthymia,” while Major Depressive Disorder was simply called “clinical depression”—a simplified framework that often led to generalized treatment approaches.

The publication of the DSM-5 marked a pivotal shift in how we classify and understand depressive disorders. “Dysthymia” became a Persistent Depressive Disorder, better reflecting its chronic nature. Similarly, Major Depressive Disorder’s criteria expanded to include various specifiers such as seasonal patterns and severity levels, acknowledging the condition’s complexity. These weren’t mere terminology changes—they represented a deeper understanding of how depression manifests differently in each person.

Distinguishing between different types of depression is crucial for effective treatment. Someone with Major Depressive Disorder might respond well to intensive short-term interventions, while an individual with Persistent Depressive Disorder typically requires long-term management strategies. This spectrum-based approach allows mental illness professionals to develop more targeted, personalized treatment plans, leading to better outcomes for those seeking help.

Rather than applying standardized solutions, clinicians can now tailor their interventions based on where an individual’s symptoms fall on the depression spectrum, considering both the type and severity of their condition.

Major Depressive Disorder (MDD): A Closer Look

Major Depressive Disorder stands as one of the most significant mood and overall mental health disorders, characterized by intense depressive episodes that fundamentally alter a person’s thoughts, emotions, and behaviors. For a clinical diagnosis, an individual must experience five or more specific depression symptoms during a two-week period, with at least one being either persistent depressed mood or loss of interest in previously enjoyable activities (anhedonia).

The intensity and duration of a major depressive episode distinguish them from normal periods of sadness. Episodes typically last for at least two weeks but can persist for months without proper depression treatment.

During these periods, major depression penetrates every aspect of daily life, creating a persistent heaviness that doesn’t lift in response to positive circumstances. Many individuals report that these episodes feel markedly different from their usual emotional state.

Physical and cognitive symptoms play a central role in MDD. Common physical manifestations include significant changes in appetite and sleep patterns, as sleep disturbances are closely linked to depressive disorders.

Cognitive symptoms often manifest as difficulty concentrating, indecisiveness, and memory problems. Many individuals experience what’s often described as “brain fog,” making even simple decisions feel overwhelming.

The impact on daily functioning can be profound. Work performance often suffers as concentration and motivation decline. Basic self-care tasks may feel insurmountable, and maintaining relationships becomes challenging as individuals withdraw from social interactions. This functional impairment often creates a cycle where reduced activity leads to increased isolation, potentially deepening the depression.

Several factors can trigger or contribute to MDD development. Genetic predisposition plays a significant role, with individuals having a family history of depression showing increased vulnerability.

Environmental factors such as chronic stress and trauma play a significant role in the development of depression, particularly in cases where PTSD and depressive symptoms overlap. Additionally, biochemical factors, including neurotransmitter imbalances in the brain, contribute to the disorder’s development and persistence.

Persistent Depressive Disorder (PDD): The Long-Term Challenge

Persistent Depressive Disorder represents a chronic form of depression, defined by a persistent low mood lasting at least two years in adults or one year in children and adolescents. For clinical diagnosis, adults must experience at least two symptoms: changes in appetite, sleep problems, low energy, poor self-esteem, difficulty concentrating, or persistent feelings of hopelessness. While symptoms may be less severe than Major Depressive Disorder, their persistent nature creates distinct challenges.

Unlike the episodic pattern of MDD, PDD manifests as an almost constant state of depression. While there may be brief periods of improvement, these rarely last more than two months. This chronic nature distinguishes PDD from typical mood fluctuations—it becomes interwoven with a person’s daily experience, often leading them to view their depressed mood as a permanent personality trait rather than a treatable condition.

The impact on relationships and career development can be significant. The persistent symptoms often strain personal relationships as others struggle to understand the chronic nature of the condition. Career progression may suffer due to constant fatigue, low self-esteem, and reduced motivation. Unlike acute depression, PDD creates a continuous undercurrent that affects consistent performance and long-term professional growth.

Living with PDD presents unique challenges in treatment and daily management. The extended duration often leads to ingrained negative thought patterns that resist change. Treatment typically focuses on developing coping strategies despite persistent symptoms rather than awaiting complete resolution. While the chronic nature of PDD requires long-term management, proper intervention can lead to significant quality-of-life improvements and better symptom control.

Related Article: Depression Checklist for Early Diagnosis

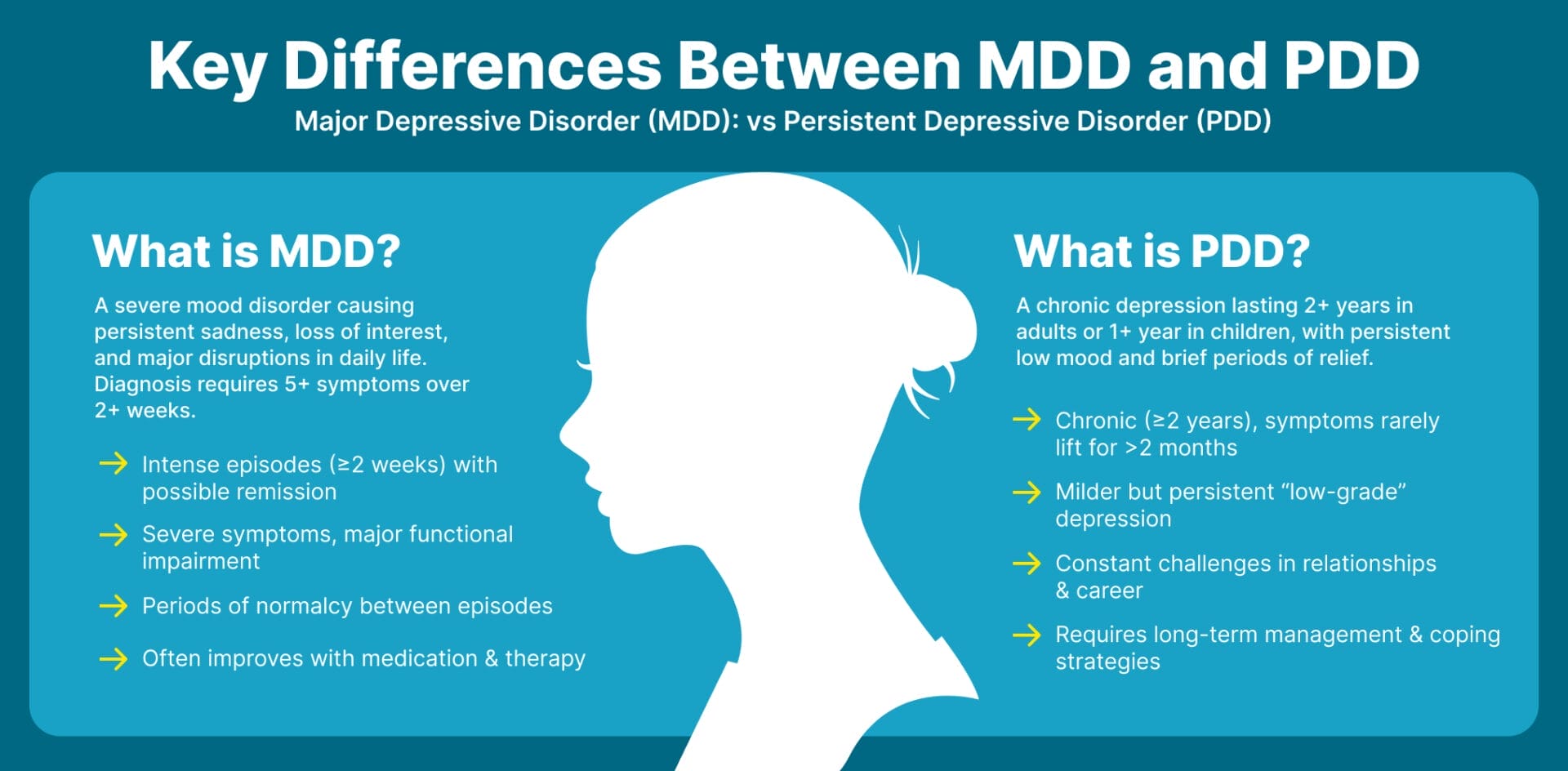

Key Differences Between MDD and PDD

While Major Depressive Disorder and Persistent Depressive Disorder share some common symptoms, they differ significantly in several key aspects. Understanding these differences is crucial for accurate diagnosis and effective treatment.

- Duration and Pattern: MDD occurs in distinct episodes lasting at least two weeks, with possible periods of remission. PDD is chronic, persisting for at least two years, with symptoms rarely lifting for more than two months.

- Severity and Presentation: MDD features more severe symptoms that significantly impair functioning. PDD presents as a milder but constant “low-grade” depression that persists over time.

- Impact on Quality of Life: MDD allows periods of normal functioning between episodes. PDD’s chronic nature creates consistent challenges in maintaining relationships and career growth.

- Treatment Response: MDD often improves with targeted interventions and medication. PDD requires long-term management strategies and ongoing therapeutic support.

- Co-occurrence: Both conditions can exist simultaneously (“double depression”), requiring more comprehensive treatment approaches.

Treatment Approaches

Effective treatment for depressive disorders, like other mental health disorders, requires a thorough, individualized approach that adapts to each person’s specific symptoms and circumstances.

Evidence-Based Interventions for MDD

Treatment typically combines psychotherapy (particularly CBT or Interpersonal Therapy) with antidepressant medications. Regular therapy sessions help identify triggers and develop coping strategies, while medications target biochemical imbalances that contribute to depressive symptoms.

Long-term Management Strategies for PDD

PDD treatment focuses on sustainable, long-term approaches, including ongoing psychotherapy and consistent medication management. Regular monitoring helps adjust interventions as needed, with an emphasis on developing lasting coping mechanisms and support systems.

Role of Residential Treatment

Residential facilities provide structured, intensive care when outpatient treatment proves insufficient. Programs offer comprehensive support, including daily therapy, medication management, and skill-building in a controlled environment designed to promote recovery.

Individualized Treatment Plans

Each plan addresses specific symptoms, co-occurring conditions, and personal history. Treatment teams regularly assess progress and adjust interventions based on response, ensuring the approach remains effective for each individual’s unique needs.

Holistic Approaches and Lifestyle Modifications

Treatment extends beyond traditional interventions to include exercise, nutrition, sleep hygiene, and stress management. These evidence-based lifestyle modifications complement clinical treatments and support sustainable recovery.

Related Article: What Are the Three Forms of Treatment for Depression?

When to Seek Mental Health Professional Help

Recognizing when to seek help for depression is crucial for recovery, yet many people delay treatment due to stigma or uncertainty about their symptoms.

Understanding the key indicators and benefits of professional intervention can help individuals make informed decisions about their mental health.

Warning Signs and Symptoms

Depression becomes clinically significant when symptoms persist for two weeks or longer, interfering with daily functioning. Key warning signs include persistent sadness, loss of interest in activities, changes in sleep or appetite, difficulty concentrating, and thoughts of self-harm.

If these symptoms disrupt work, relationships, or self-care, professional intervention is needed.

Benefits of Early Intervention

Early treatment improves outcomes and prevents symptom escalation. Professional help can interrupt negative thought patterns before they become entrenched, reducing the risk of chronic depression. Early intervention also helps prevent secondary problems like relationship difficulties or career setbacks.

How Residential Treatment Facilities Help

Residential treatment becomes appropriate when outpatient care isn’t sufficient or when individuals need a structured environment for recovery. These facilities provide intensive therapy, medication management, and 24/7 support. They’re particularly beneficial for those with severe symptoms or when home environments aren’t conducive to recovery.

The Diagnostic Process

Initial evaluation involves comprehensive interviews about symptoms, medical history, and stressful life events. Clinicians use standardized assessments to determine depression type and severity. This process helps create targeted treatment plans and may include medical tests to rule out underlying health conditions.

Hope and Healing: Your Path Forward

Living with depression—whether MDD or PDD—can feel like carrying a heavy weight that others can’t see. But you’re not alone, and you don’t have to figure this out by yourself. Taking that first step to reach out for help might feel daunting, but it’s also incredibly brave and could be the beginning of your journey toward feeling better. At Kinder in the Keys, you’ll find compassionate care and a supportive environment designed to guide you toward healing and renewed hope.

Remember, both conditions are treatable, and with the right support and personalized approach, many people find their way to better days, stronger relationships, and renewed hope.